What is the CHIPS Act, and Will it Fix the Semiconductor Supply Chain Issues?

By Craig McClure, Senior Trade Advisor, Braumiller Consulting Group

Unless you’ve been living on a lost island in the South Pacific, you are no doubt aware of the shortage of semiconductors. The shortage and supply chain issues have been highlighted in media reports that feature video images of parking lots and fields full of partially assembled automobiles at many U.S. auto manufacturing locations. The pandemic-driven shift to remote working and schooling, home-centered entertainment such as binge-watching shows on Netflix and playing video games on Play Stations, added to the chip shortage due to the unprecedented demand for devices to support these activities.

The chip shortage put a spotlight on the US semiconductor industry and how relatively small the production capacity is in the country where the semiconductor was invented. Of greater concern is that production of the more complex and widely used logic and memory[1] chips is concentrated in countries such as China, Taiwan, and South Korea. This region is exposed to natural disasters such as earthquakes, geopolitical frictions, and water and power shortages.

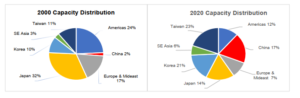

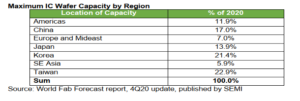

It was not always this way, from the mid-1980’s through late 1990’s Japan and the Americas dominated global semiconductor manufacturing, accounting for over 70 percent of production and sales in the 80’s into the early 1990’s. However, the trend of off-shoring production to take advantage of lower production costs initiated the shift to Asia-Pacific countries such as South Korea, China, and Taiwan. In addition, some governments in these countries offered financial incentives to foster growth of semiconductor production in their nations. According to data from SEMI[2] the United States produced 24% of the worlds’ semiconductors in 2000 but by 2020 US production had dropped to 12%. Conversely, Asia-Pacific countries saw dramatic production increases. For example, Taiwan’s 2000 production accounted for only 11% of global production but by 2020, they held the global lead at nearly 23 percent of total production.

As a result of the supply chain issues that impacted the U.S. consumers and businesses during the pandemic, President Biden issued an Executive Order (“EO”) on February 24, 2021 establishing a new policy directive that the United States needs “resilient, diverse, and secure supply chains to ensure our economic prosperity and national security. From the President: Therefore, it is the policy of my Administration to strengthen the resilience of America’s supply chains.”

Key directives in the EO included a 100-day Supply Chain Review requiring the heads of multiple agencies to submit reports to the President outlining risks in the supply chains of several industries. This included a specific requirement for the Secretary of Commerce to submit a report identifying risks in the semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging supply chains and policy recommendations to address these risks. To support this requirement, Commerce published a Notice of Request for Public Comments in the Federal Register on March 15, 2021 seeking comments on Risks in the Semiconductor Manufacturing and Advanced Packaging Supply Chain. The notice solicited comments and information related to the policy objectives from Biden’s EO as they effect the U.S. semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging supply chains.

130 comments were received by Commerce from which the Secretary produced the EO-required “100-day” report. The 61-page report includes significant input from industry commenters including detailed explanations of the global nature of the industry and the risks faced by the industry. Among the recommendations contained in the report were for government to promote investment, transparency, and collaboration with industry to address the semiconductor shortage and to fund the CHIPS act. It also supports a policy aimed at assuring there is a well-trained workforce.

The Biden administration has taken steps to implement these recommendations with perhaps the most notable being the passage of the CHIPS act which the President signed into law on August 9, 2022. The act represents a $50 billion investment to spur long-term growth in the domestic semiconductor industry to support national and economic security.

The CHIPS Act includes $39 billion in tax benefits and other incentives to encourage companies to build new chip manufacturing plants in the US. Over half of the money is to be used to re-shore production of logic and memory devices while some of the funds will be used to re-shore production of lower-tech chips used in cars, communications, medical devices, and defense products. Currently, many US fabless semiconductor companies outsource chip manufacturing to off-shore foundry companies. For example, Taiwan-based companies account for 73% of the market share for contract-based semiconductor production as of 2021. The heavy reliance on Taiwan foundries presents a significant risk to the US especially in light of the China risk. CHIPS funding includes a 25% investment tax credit which should close the gap between the cost of building fabs in the U.S. and other countries like Taiwan which should incentivize construction of foundries in the U.S.

The remaining $11 billion will fund the creation of the National Semiconductor Technology Center (NSTC), the National Advanced Packaging Manufacturing Program (NAPMP), up to three new Manufacturing USA Institutes, and in NIST metrology research and development programs.

The NSTC will be a public-private entity comprised of industry, universities, the Departments of Defense and Energy, and the National Science Foundation to conduct research, provide prototyping capabilities, establish an investment fund, and expand workforce development programs. One could argue that the latter is one of the most important objectives of the CHIPS act. Employment in the U.S. semiconductor industry has been steady since 2009 at about 185,000 workers with new hiring mainly as a result of replacing workers lost through attrition[3]. The workforce additions required to support the construction and operation of the new fabs will increase significantly. According to the Commerce Department’s “A Strategy For the Chips For America Fund”, an $8 billion investment may be needed over the next 5 years to substantially address the industry’s workforce needs. The NSTC will coordinate and scale up the ongoing workforce development and recruitment efforts such as those currently done by industry associations, employers, state/local governments, and federal agencies to achieve maximum effectiveness. If it fails to grow the workforce, it won’t matter how many new fabs are built if there are no workers to staff them.

The CHIPS act also funds the creation of the National Advanced Packaging Manufacturing Program (NAPMP). At the completion of the wafer fabrication process, the individual die are packaged in a manner which facilitates the ability to attach the individual chips to printed circuit boards which ultimately end up in electronic products used by consumers. Conventional methods are labor intensive which lead to the off shoring of this critical step in the semiconductor production process to Asia. It would be economically challenging to re-shore this process back to the U.S., however, the NAPMP is focused on developing a U.S.-based advanced, next-generation, packaging capacity including substrate production, heterogeneous integration, and the ability to work with and incorporate diverse new material systems. It is estimated that the U.S. can achieve 50% of the advanced packaging market by 2024[4].

In addition to the NIST and the NAPMP, there is also the CHIPS Program Office (CPO) which is the operational unit charged with implementation and oversight of the program and to provide policy and stakeholder engagement support across the program offices.

The CHIPS act is a step in the right direction to mitigate the risk to the US and should be effective in achieving a sustainable and secure supply chain of chips. However, the semiconductor production process is a complex, and mature global eco-system. $50 billion falls well short of what it would take to fund a totally closed-loop semiconductor production industry in the US. In the comments submitted by the Semiconductor Industry Association[5] on April 5, 2021, in response to the Commerce department’s request for comments they cite that for a fully “self-sufficient” local semiconductor supply chain to be established would require “at least $1 trillion in incremental upfront investment” which would result in up to a 65 percent increase in the price of semiconductors resulting in higher prices for electronic devices at the consumer level.

CHIPS will be helpful to fund the construction of new, and expansion of, existing semiconductor fabrication facilities, or “fabs”. In fact, according to the White House-released fact sheet on the CHIPS act published on August 9, 2022, Micron announced plans for a $40 billion investment in memory chip manufacturing in the U.S. and Qualcomm and Global Foundries announced a partnership to invest $4.2 billion for an expansion of Global Foundries’ New York state fab. In addition, Intel, Texas Instruments, and Samsung recently broke ground on new fabs in the United States, which typically take 3 years to complete the building structure, support equipment and utility installation, and production equipment install and start-up. TSMC, the Taiwan-based dominant player in the foundry segment recently completed construction of its new fab in Arizona and is slated to begin mass production in Q1 2024.

However, there are required inputs and materials that are not widely available from U.S.-based suppliers and given economies of scale inherent in the global value chain developed over the past 3 decades, foreign sourcing of these will likely continue. For example, silicon wafers are the dominant starting substrate for production of semiconductor devices. These wafers are made from high-purity silicon required to create the atomic lattice structure critical to the process. The wafer market is dominated by four companies, two in Japan, one in Taiwan, and the other in South Korea. The Japanese companies have U.S.-based wafer-manufacturing facilities but the output of both 200mm and 300mm wafers is less than 10% of total global demand[6]. The investment required to increase wafer production in the U.S. is substantial and is a disincentive to the prospect. Likewise, there are chemicals and rare earth minerals used in the process which are either 100% foreign-sourced or from domestic single source providers.

To mitigate the risk of the global supply chain, the CPO will play a key role in engagement, with other agencies and Commerce department bureaus, to engage and collaborate with allies to assure supply chain resiliency. Transparency of market conditions, including disclosure of public investments and supply chain disruptions will aid in risk mitigation oversupply and ensure that U.S. investments in manufacturing and R&D are on target. Other desired outcomes of the collaboration with allies is a reduction in geographic concentration in upstream materials and downstream industries.

Commerce has published guidelines for applicants interested in CHIPS funding and is targeting early February 2023 to start accepting and reviewing applications and could start releasing funds by next spring. Still, it will take a few years before domestic production gains are reached given the typical 3-year cycle from ground breaking to production startup. In addition, the increased demand for semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME)will likely cause additional delays in production startup. SME suppliers are faced with the same supply chain issues as the equipment itself is full of semiconductor devices. However, if the CHIPS act meets its goals, it will go a long way towards reducing the semiconductor supply chain vulnerability the U.S. is currently exposed to.

[1] Logic semiconductor devices include highly sophisticated chips that serve as the main processor for electronic products such as PC’s, smart phones, etc. Memory semiconductors include RAM and NAND data storage devices as well as SD cards.

[2] SEMI is the industry association comprised of more than 2400 worldwide members that are engaged in all aspects of semiconductor production including manufacturing, equipment providers, design, and materials. Data in this report was submitted by SEMI in its response to Commerce’s request for information on the semiconductor supply chain risks. (www.semi.org)

[3] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Current Employment Statistics dataset. This 185,000 figure represents semiconductor manufacturing jobs only. 277,000 people are employed in the broader semiconductor industry, including manufacturing, design, and related fields.

[4] “Reshoring Advanced Semiconductor Packaging: Innovation, Supply Chain Security, and US Leadership in the Semiconductor Industry,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology, June 2022

[5] The Semiconductor Industry Association (“SIA”) is the Voice of the U.S. Semiconductor Industry helping to advance policies that help the industry grow and unite semiconductor companies around common challenges. (www.semiconductors.org)

[6] This data reported by SEMI in its April 5, 2021 submission to Commerce on Risks in the Semiconductor Manufacturing and Advanced Packaging Supply Chain Notice of Request for Public Comments.