As you sip your frothy Cappuccino while basking in the glow of your most recent quarterly report which shows a dramatic increase in sales in your China division….your assistant bursts into your office with a letter from….the Department of Justice!!!…hmmm….I wonder what they want???

While Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in China has lost some momentum, having decreased from $116 billion to $111.7 billion from 2011 to 2012, China still remains one of the most preferred locations for corporate investment. Along with these investment opportunities, some multi-national companies such as the British pharmaceutical giant Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK) are finding themselves in the headlines faced with allegations of violations of the FCPA[1] and Chinese anti-bribery laws.

When a multi-national decides to enter China through FDI several underlying forces could negatively impact the organization:

- Corruption that has long been the norm in China

- The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) of 1977 is now vigorously enforced by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ),

- The existence of state owned entities (SOE) that appear to be private entities

Corruption in China

Although China is attractive for FDI, multi-nationals must know with whom they are doing business, and be aware of the inherent risks of corruption. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) ranks China a relatively poor 39th.[2]

With regards to corruption risk, what would a multi-national expect when doing business in China? In the GSK case, the company is being investigated by Chinese authorities for colluding with a travel agency to funnel money to government doctors using fraudulent invoices.[3] In 2012 Eli Lilly had similar issues as its sales force was submitting expense reimbursements used to get cash to pay for bath houses and meals to government doctors in China in return for the doctors purchasing Eli Lilly products.[4]

The Pharmaceutical industry is not alone in struggling with corruption in China. In 2012, Morgan Stanley’s real estate and fund advisory Managing Director, Garth Peterson, colluded with a former chairman of a Chinese state owned enterprise, Yongye Enterprise Group. They paid each other “finder’s fees” of $1.8 million that Morgan Stanley owed to third parties. In exchange for the fees and personal interest in Morgan Stanley’s investments, the Chinese official brought business to Morgan Stanley. [5]

FCPA Defined

The condensed explanation of the FCPA is the prohibition of paying a foreign official anything of value to obtain business. The SEC and DOJ have interpreted the FCPA broadly in its definition of a “foreign official” and the giving of “anything of value.” These interpretations are even more significant with regards to China.[6]

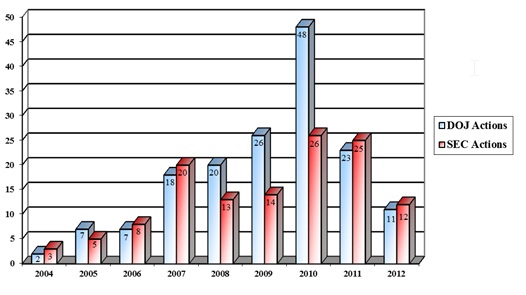

Although the FCPA has been a federal statute since 1977, the last 10 years has shown a dramatic increase in enforcement activities by both the SEC and the DOJ for both public traded entities on the United States stock exchanges and US Domestic Concerns which are privately held entities.[7]

Despite the most recent decrease from 2011 to 2012, the DOJ has sent out an FCPA Guideline to demonstrate its focus of continued rigorous enforcement. [8] The DOJ and SEC continue to bring cases against companies for bribery in China.

State Owned Entities in China

Before China’s economic reforms in 1978, China’s were similar to the pre-1990’s Soviet economy where state owned entities dominated the major industries and were commanded and controlled by the central government. Although economic reforms have decreased their share of total economic output (80% pre-1978 and 15% post millennium), the state owned entities are a major contributor to the industries such as oil and gas, steel, telecom, banking and transportation. [9]

What multi-national companies may not know when entering into FDI in China via joint ventures, acquisitions or other business arrangements, is that many seemingly private companies in China may be state owned entities,’ and have government ties and political officials as employees or owners. The DOJ and SEC, as mentioned earlier, have a broad interpretation of state owned entities and foreign officials. In United States vs Carson, the DOJ charged Carson with paying bribes to foreign officials in China, including the China National Offshore Oil Company, Dongfang Electric Corporation and Petrochina. Carson claimed that a state owned entity is not an instrumentality of the government, and therefore its employees cannot be foreign officials. The court set forth several factors to determine whether a company is an instrumentality of the government, and overruled Carson’s motion to dismiss stating that the state owned entities in question were instrumentalities of the government. [10]

Foreign Official in China

The definition of a “foreign official” in China can be more encompassing than in other countries. Continuing with the DOJ and SEC’s broad interpretation of elements of the FCPA, a “foreign official” in China could include the large population of Communist Party of China (CPC) members. The CPC runs parallel to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in terms of structure and membership. The two entities are difficult to separate and appear to be indistinguishable.[11] CPC members may have businesses in the private sector and if an MNC does business with, or acquires the CPC owned company or CPC employee, that CPC member may use political connections/favors to obtain business.

Compliance Roadblocks

Most multi-national companies doing business abroad rely on a thorough “due diligence” to surface or avoid FCPA issues. While due diligence is essential, in practice it has become increasingly difficult in China. As of January 2013 the Chinese Government put a halt on the free accessibility of corporate records kept by the Administration of Industry and Commerce (AIC). The AIC is a regulating body that keeps financial, and ownership information on all companies in China. This restriction to corporate information was a response to several publications of fraudulent Chinese companies and political figures by the media and investment informational companies. [12] This restriction will create serious difficulties in investigating the following:

- Determining the ownership interest of potential joint ventures, vendors, clients to identify possible state owned entities, foreign officials, politically exposed persons (PEP lists)

- Proactive fraud detection / data analytics – matching addresses and telephone numbers of vendors, clients and employees to identify shell companies

- Potential investors that want to conduct due diligence on Chinese companies

FCPA/Anti-Fraud Compliance Programs

It should be apparent to any company considering or participating in FDI in China that the cost of compliance should be greater than zero. “Top down” style corporate level compliance programs are unlikely to be effective in addressing these risks. While a robust global anti-corruption program is important, dealing with high-risk countries such as China requires compliance programs that must be implemented and overseen at the local level. This will require a program to be tailored to the particular risks and culture of that local area, as well as having compliance personnel in country.

At the very minimum, a robust and effective compliance program in China should include the following:

I. Training for high risk employees

- Employees such as sales or purchasing personnel that are working and or living in China must have a thorough understanding of FCPA and local country anti-bribery laws

- The training would include case study and possibly simulations of how an employee might be approached to pay a bribe.

- It is vital to educate employees on not only what bribery entails but the penalties, fines and punishment of not only the company but the employees that commit the act. Reporting the violations to the appropriate law enforcement agency will also be a strong deterrent. Employees will more likely become compliant if they know that their employment and livelihood (not being charged /convicted of a crime) depends on their compliance not just because it is illegal in the United States.

- Employees must understand that if they observe violations that it is their responsibility to report it and know how to report the potential violations.

- Training must be ongoing and updated based on new examples of possible bribery situations.

- Training must be tailored to local language, culture and country specific fraud/corruption issues.

II. Incorporate into other related compliance programs

- Where possible, FCPA compliance activities should be built into an overall anti-fraud and regulatory compliance program, such as international trade compliance, ITAR and general fraud (e.g. fraud, embezzlement, and theft of trade secrets). From a legal perspective, issues associated with FCPA are distinct from other regulatory areas such as ITAR and EAR, in practice; they share many parallel issues, compliance activities and penalties. Integration of similar compliance activities is logical, more cost effective, and more likely to be effective than multiple independent stand along activities.[13]

III. Communicate Anti-Fraud program

- Communicate on a local level, preferably facility by facility that the company has a “zero tolerance” for violations of anti-fraud policy. It should be made clear what is expected of each employee with regard to compliance, specifically how to report potential wrong-doing, and the consequences to each employee for failure to live up to those expectations. This should take the form of local training and written policies provided regularly to employees and distributed to company partners/vendors/clients.

IV. Due Diligence on Potential Business Relationships in China

With the recent limitations on obtaining basic company records in China, due diligence has become more difficult. It is nonetheless still required as a basic element of an effective compliance program.

- Due diligence must be conducted locally using reputable companies. The cost of local due diligence can be high, therefore prioritizing based on the type of FDI in China is recommended.

- Be wary of firms offering to “certify” business partners as being FCPA compliant. These certifications are typically the result of a partner’s “self-reporting” to the certifying organization. These certifications offer little meaningful insight, and no guarantee of compliance. Instead, use firms specializing in due diligence that use trained investigators and independent data to validate assertions.

- All contracts, agreements, policies, and other documents (e.g. code of conduct) must explicitly require compliance with all applicable laws and regulations. Contracts and agreements must always include a right to audit and indemnity clauses.

V. Proactive Fraud Detection Testing:

In broad terms, proactive fraud detection refers to a set of programs, tools, and tests designed to surface high risk transactions rather than waiting for them to be discovered through other means. The topic of proactive fraud detection is broad and beyond the scope of this article. However, the following are some illustrative examples in the FCPA context:

- Proactive testing includes data analytics and standard fraud testing. The key is to leverage local data sets/accounting records in the high risk areas and tailor the testing to frauds commonly encountered in those areas. For example:

i. The Eli Lilly case involved sales employees submitting fraudulent expense reimbursements to disguise cash payments to doctors. A company concerned about such activity could analyze trends in expense categories prone to manipulation (e.g., miscellaneous, cash advances, entertainment, meals, gift cards) and/or benchmarking against similar industries to identify high risk transactions.

ii. GSK’s investigation involves use of a third-party vendor to disguise illegal payments. Companies might address this issue by analyzing accounts payable vendor master files to identify either large or frequently recurring payments in historically high risk services such as consulting, travel, legal and professional fees. Any suspicious transactions would then be compared to documentary evidence and investigated further.

iii. Where companies source vendors by competitive bid, data analysis of the vendor master file can identify suspicious trends in vendor success rates or high rates of change orders/cost overruns, both potential indicators of bid rigging.

iv. Companies can establish almost unlimited automated tests tailored to flag unusual transactions for further review. Large commission payments, payment records with certain key words, payments made in non-local currency or sent to different locations, are just some of the examples companies use in proactive fraud detection.

Final Comments

Companies that recognize the risks and invest in realistic, practical, and robust compliance programs will realize significant financial benefits including:

- Reducing direct expenses associated with corruption or fraud (e.g. elimination of illegal payments) by educating and deterring employees from engaging in such activities,

- Reducing the costs of investigations by deterring or identifying fraud/corruption early,

- Reduce the cost of potential fines (or even imprisonment) by identifying and self-reporting.[14]

China is certain to continue to be a huge opportunity for FDI. In order to be successful in this market, multi-national companies must understand that the significant investment in FCPA and anti-fraud compliance is an essential part of their overall strategy. U.S. and local regulators recognize that companies operating in China and other high-risk locations are fertile ground for fines and penalties. The enforcement of FCPA and local anti-bribery laws continues to increase.

Post Script

It is worth reviewing the Morgan Stanley FCPA case. Morgan Stanley cooperated completely and was investigated vigorously. Its compliance program had identified Yongye Enterprise Group as a state owned enterprise and notified Mr. Peterson some 35 times. Mr. Peterson ultimately ignored the warnings and disregarded the company’s policies. He has been charged criminally for his violations of FCPA and the Investment Act. However, regulators declined to charge Morgan Stanley as it had an effective compliance program in place, conducted a thorough investigation when the matter was discovered, and fully cooperated with authorities. The impact of this decision is a savings of many millions of dollars in investigation costs, legal fees, and potential fines and disgorgements.[15]

If the DOJ and SEC want to continue to collect fines and penalties and grow their budgets they will probe into the companies that are investing heavily in the high risk countries like China where ease of business is high. If you do not want to be the manager that just received the DOJ letter, compliance is the key.

By: Fidelity Forensics Group LLC

Mark Jenkins CFE, mjenkins@fidelityforensics.com

Sunny Chu CPA, CFE, schu@fidelityforensics.com

Christopher Meadors CPA, and JD, cbmeadors@fidelityforensics.com

[1] The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) prohibits the paying of a foreign official with anything of value to obtain or retain business.

[2] Zero means highly corrupt and 100 means limited corruption. To provide points of reference, Afghanistan and Somalia are 8 on the CPI and Denmark and Finland are 90. Although China is not the highest in corruption, it remains a high-risk country.

[3] New York Times, July 11, 2013, “GlaxoSmithKline Accused of Corruption by China”

[4] Id New York Times

[5] SEC Charges Former Morgan Stanley Executive with FCPA Violations and Investment Adviser Fraud, http://www.sec.gov/News/PressRelease/Detail/PressRelease/1365171488702#.Uh39ej-gSkQ

[6] § 78dd-1 [Section 30A of the Securities & Exchange Act of 1934].(a) Prohibition

[7] http://www.gibsondunn.com/publications/pages/2012YearEndFCPAUpdate.aspx

[8] http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/guide.pdf

[9]CHINA UNDER THE FOREIGN CORRUPT PRACTICES ACT, by Daniel Chow p. 580-581

[10] Id p. 579

[11] Id p. 587

[12] Exploring the impact of China’s clampdown on public records, MAY 2013, “The Fraud Examiner”, by Peter Humphrey, CFE

[13] ITAR deals with military technology which could entail military technology sales directly to foreign governments or through local brokers which inherently would include foreign officials. This is an FCPA red flag in the making!

[14] In determining fines and penalties, DOJ and SEC will consider the entity’s compliance program, whether they self-reported, and how sufficiency of the company’s investigation.

[15] By way of example, Wal-Mart recently disclosed that its own FCPA investigation costs had reached $230 million as of March of 2013, equating to approximately $600,000 per day in professional fees, and has continued to grow. Wal-Mart has not yet been assessed penalties or fees related to the matter.