According to Gabriel Lozano, J.P. Morgan’s chief economist for Mexico, until recently, China had been much more attractive to industry being cheaper, more flexible, and more accommodating; but wages in China are steadily rising, putting cost pressure on manufacturers. Lozano states, “Mexico didn’t start to win the battle against China until we started the recovery from the recent recession.”

As noted, the average salary for Mexican workers was $2.10 per hour in 2011, up 19 percent from $1.72 in 2001. By comparison, the average wage in China swelled during those years to $1.63 per hour in 2011 from 35 cents per hour in 2001. Thus, the difference between labor costs in Mexico and China is a moot point.

There’s also, of course, the cost advantage of proximity (near-shoring). With higher fuel prices constantly looming on the economic horizon, obviously manufacturers worldwide are seeking opportunities to manage shipping costs by producing goods close to their market. Case in point being the 3,000+ maquiladoras humming along with daily output along Mexico’s northern border with the U.S.

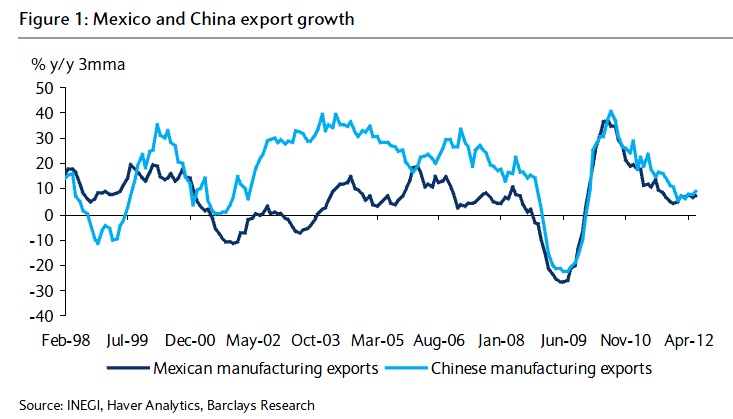

Today, it costs roughly $5,000 to ship a container from China to the U.S., compared with $3,000 to truck the same freight in from Mexico, says Lozano. “We expect that trend to continue and build into 2013 and 2014,” he said. Marco Oviedo from Barclays, joined in with a research note that concludes, “after lagging Chinese manufacturing exports for a decade, Mexico has taken the lead post-2008-09. We believe this change is likely to be structural and persistent.” It would not be accurate to say that Mexico is taking the lead, but the trend is obvious; Mexican manufacturing is on the upswing.

Roughly 80% of Mexico’s exports went to the United States in 2011, and exports constitute more than 30% of Mexican gross domestic product (GDP)—which means that the United States generates a quarter of Mexico’s economic activity. Over the past two years, the United States has been a good export market because its economy has been one of the most stable globally.

Geographical proximity to end markets, or near-shoring, is becoming more desirable for two reasons:

A) The rising price of oil has driven global transportation costs higher in recent years, and manufacturers want to be able to adapt quickly to market changes.

B) Near-shoring has helped Mexico’s manufacturing sector, helping grow the country’s market share in goods that are expensive to ship because of their bulk or weight, such as televisions, major household appliances and automobiles.

Another factor contributing to Mexico’s growing market share is its workers’ advances in areas that require higher skills, such as cars, telecom equipment and aerospace. The labor-cost equation is also moving in Mexico’s favor, according to the Boston Consulting Group (BCG). One in two thousand Mexican factory workers earned more than four times as much as Chinese workers. Due in large part to China’s double-digit wage increases in recent years, by 2010, Mexican workers earned only 1.5 times as much. BCG estimates that by 2015, the fully loaded cost (including benefits, taxes and indirect costs) of hiring Chinese workers may be 25% higher than hiring Mexican workers.

Barclays provides interesting and detailed analysis of Mexico’s productivity gains in recent years, including areas in which it has started to specialize, and in which it has comparative advantages. Just a handful of examples are transport equipment, telecommunications equipment and automotive parts.

For example: General Motors, the largest automaker in the U.S., announced last year it would invest some $540 million to expand its plant in Toluca, Mexico, and joined a growing list of manufacturers seeking an attractive manufacturing arrangement south of the border. Therefore, with lower shipping costs and increasingly competitive wages, Mexico is enjoying a manufacturing boom, attracting billions of dollars in foreign investment from firms that are building factories to supply the North American market.

Recently, automakers Nissan, Audi, Honda and Mazda have all announced plans to open plants in Mexico over the next few years. Italian tire maker Pirelli & C. said earlier this year it would invest $300 million in new factories in Mexico by 2015, and Swedish appliance maker Electrolux moved a plant last year from Webster City, Iowa to Juarez, Mexico.

Blue-chip aluminum producer Alcoa also expanded its facility in Acuna, Mexico, joining U.S. companies already producing there, such as General Electric, Honeywell, and Hawker Beechcraft.

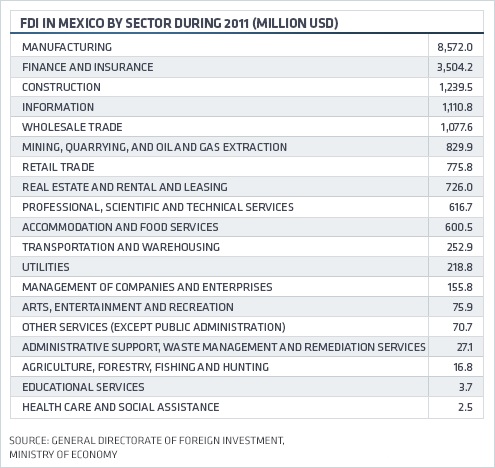

Foreign direct investment, or FDI, in Mexico reached $19.4 billion in 2011 — with nearly half of that total destined for the manufacturing sector, according to the Mexican Ministry of the Economy.

“FDI in Mexico has fully recovered from the post-2008 decline, and we anticipate continued strength in manufacturing from autos and aerospace to keep up with U.S. and world demand,” writes Sergio Martin, the chief economist on Mexico for investment banking firm HSBC in his 2012 report on the Mexican economy. “Until very recently, China had been cheaper, more flexible and more accommodating to industry, but wages in China are rising at a remarkable pace, putting cost pressure on manufacturers,” he said. “Mexico didn’t start to win the battle against China until we started the recovery from the recent recession,” according to Gabriel Lozano, J.P. Morgan’s chief economist for Mexico.

A 2012 survey by global business advisory firm AlixPartners in New York found that those manufacturing companies considering near-shoring indicated Mexico was overwhelmingly the most attractive location from which to operate — ranking it higher than any other country in the Americas, including the United States.

Despite widely publicized security risks stemming from the drug wars, the survey revealed another 43 percent of companies considering offshoring their existing U.S. operations also indicated that Mexico is their top choice, with China in second place at 30 percent.

With manufacturing exports growing at current rates, one could expect Mexico to displace China as the top U.S. trading partner by 2018, as China’s labor cost advantage shrinks.

Written by Bob Brewer, Contributing Writer